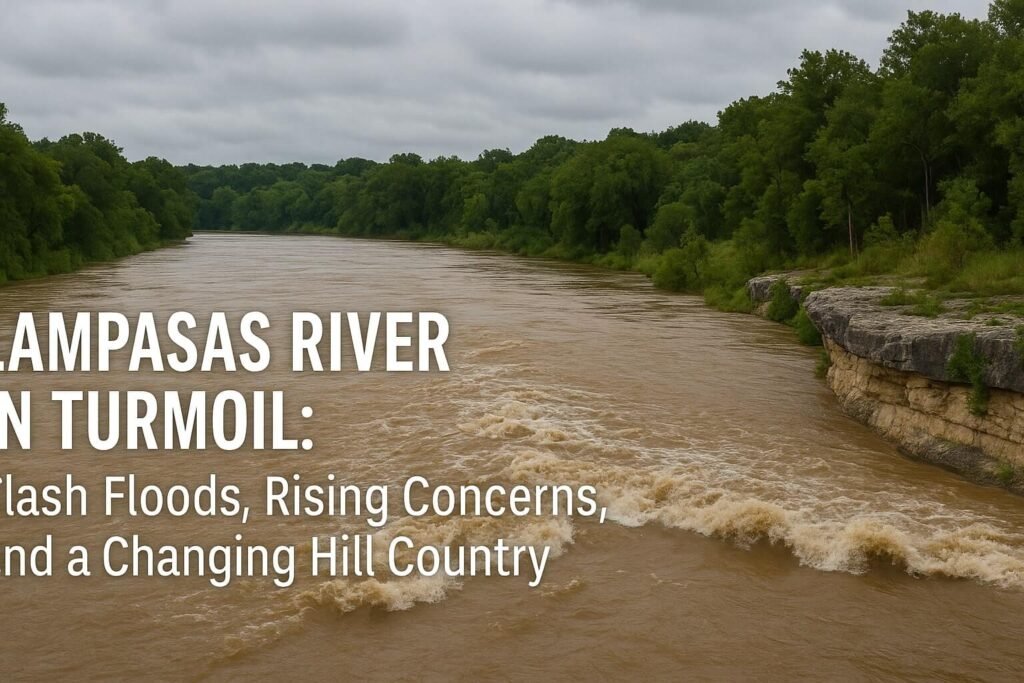

The Lampasas River, a name that usually rolls gently through Central Texas maps and Sunday kayaker stories, has just become the center of attention. In the span of 24 hours, it morphed from a quiet, meandering stream to a churning, flood-swollen force that surged past its banks, crested at a jaw-dropping 33 feet, and stunned even seasoned river watchers. The town of Lampasas, built along this deceptively tranquil waterway, witnessed one of its highest floods in recent memory over the weekend of July 13, 2025.

What caused this dramatic change? It wasn’t just one cloudburst. It was days of saturated soil, a heatwave broken by an intense thunderstorm cluster, and geography that tends to funnel water quickly. As the Lampasas River overflowed at record speed, it turned highways into brown torrents, flooded creeks into debris-filled walls of water, and caused damage from Kempner to Belton. But beneath the headlines, there’s a deeper story about how the river flows, how it’s monitored, and how long-term problems like bacteria and land development are silently reshaping it.

A River That Reacts Fast

The Lampasas River begins in Mills County and cuts a winding path southeast through Hill Country terrain, collecting runoff from ranchland, highways, and growing towns like Killeen and Copperas Cove. It eventually flows into Stillhouse Hollow Lake, a vital water reservoir for the region. Along the way, it gets monitored at several USGS gauges, including the one at Kempner which recently captured an astonishing 27-foot rise in a single night.

The flash flood hit its peak on July 13 when the river swelled to 33 feet at Lampasas, far beyond its usual summer trickle of 1 to 2 feet. That spike was well above the 18-foot mark that defines major flood status. With soil already soaked from above-average rainfall earlier in the year, the fresh downpour had nowhere to go but downhill, fast.

Storm chasers like Reed Timmer were on scene capturing video of the river’s explosive surge. It wasn’t just a gentle overspill. It was violent and dangerous. Vehicles were swept away. Low-water crossings disappeared. Festivals like the Spring Ho kayak race had to be cancelled. Flash flood warnings were activated across Lampasas County and beyond, and the broader Hill Country flood disaster claimed lives in other watersheds that same weekend.

But the crisis isn’t just about rising water. The Lampasas River faces longer-term risks that often go unnoticed until a disaster hits.

Pollution, Progress, and Pressure

For decades, the Lampasas River has battled bacterial pollution. In 2002, it was officially listed as impaired for high levels of E. coli, particularly in its upper segments. That bacteria doesn’t always come from a single pipe. It creeps in from many places, especially aging septic systems, livestock runoff, and feral hog activity. Since then, local organizations, landowners, and the state environmental agency (TCEQ) have teamed up to fix it.

A Watershed Protection Plan has been underway for more than ten years. It focuses on practical fixes: repairing broken septic systems, encouraging ranchers to manage runoff, hosting workshops for residents on stormwater and erosion. The goal is to reduce pollution before it hits the river. Funding comes from state and federal grants. Volunteers collect monthly samples, and there’s cautious optimism that the river is slowly healing. But every big rain still flushes trouble into the flow.

Another quiet but growing concern is the region’s development boom. New homes mean more pavement, less sponge-like soil, and faster runoff. Towns like Killeen and Copperas Cove are expanding, and even Lampasas is seeing suburban-style growth. This creates a double challenge: more flood risk and more pollution, especially when drainage isn’t thoughtfully designed. Some local leaders are now exploring low-impact development rules to balance growth with watershed health.

What Happens Next

As July unfolds, weather models hint at more rain, and the ground remains saturated. That means even small storms could spark new rises in the Lampasas River. Stillhouse Hollow Lake managers continue adjusting reservoir releases to balance water supply and flood safety. People living near the river should stay alert, especially around crossings that look shallow but can hide deadly current.

Long-term, the success of this watershed depends on cooperation. Whether it’s ranchers installing buffer strips, towns investing in smart drainage, or residents reporting failing septic tanks, every piece helps. The Lampasas River can be wild when it wants to be, but with care, it can also be safe, clean, and resilient.

What this month made clear is how fragile that balance is. In Texas, rivers don’t just flow. They rise. They flood. They test us. And when they calm again, they quietly wait to be understood.